I know - I am far behind my posts again. But I have some excuses. As I did not want to throw in just some meaningless words I need to find some time in between my other work to do some research and write about some things which might be of interest for you.

I want to continue with the series about the colour green. Let's go a bit into technical details i.e. into the rules of mixing colour and how the human vision works:

"Allegedly the physical world is achromatic. The human being can perceive light of various lengths between 400 and 700 nanometers as colours.Within the retina of the human eye there are colour sensitive photoreceptors in 3 different types. They are sensitive to 3 different wavelengths of the light, i.e. for short-wave, middle-wave and long-wave light. Short-wave light we see as blue, middle-wave light as green and long-wave light as red.Red, yellow and blue make up the primary colours in a painter's colour wheel. This system, RYB is used in art and art related areas and was the prequel of the modern scientific colour theory.

If the light is composed from two different wavelengths we will see cyan if the combination consists of short-wave and middle-wave light, yellow if we see a combination of middle-wave and long-wave light and magenta when the light is a mixture of long-wave and short-wave light. We will see white when all three wave-lengths are combined in equal parts and intensity. If no electromagnetic waves of the colour spectrum strikes the photoreceptors of the human eye (no light) we will see black.

This means the human eye has a maximum of 8 different extreme colour perceptions. They are the cornerstones and are therefore called the elementary colours."

(translated from http://www.ipsi.fraunhofer.de/~crueger/farbe/farb-wahr.html)

But painters have always used more than the 3 primary colours and used green as the fourth primary although it is mixed from yellow and blue. Why is this so?

There are 2 major principles for mixing colours: additive mixing of colours and subtractive mixing of colours.When you use additive mixing you normally use light for mixing colours which are red, green and blue. When no colours are showing the result is black - when all colours are used the result would be white. Red and green create yellow, red and blue would turn into magenta. Additive mixing of colours is used in television and computer monitors.

(original image source: http://www.ipsi.fraunhofer.de/~crueger/farbe/farb-misch.html)

The second principle of mixing colours is called subtractive mixing.

"Subtractive mixing is done by selectively removing certain colors, for instance with optical filters. The three primary colors in subtractive mixing are yellow, magenta, and cyan. In subtractive mixing of color, the absence of color is white and the presence of all three primary colors is black. In subtractive mixing of colors, the secondary colors are the same as the primary colors from additive mixing, and vice versa. Subtractive mixing is used to create a variety of colors when printing on paper by combining a small number of ink colors, and also when painting." (after Wikipedia)

(original image source: http://www.ipsi.fraunhofer.de/~crueger/farbe/farb-misch.html)

Now comes the "paradox":

Additive colour mixing, f.e. red and green combined result in yellow, or blue, red and green making white seems to fight against the human common sense i.e. vision because anyone knows that if you mix yellow and blue paint you will receive a green paint! The reason for this is that the wavelengths of light that reach the eye are often selected through more intuitive subtractive processes: for example, cyan paint appears to our eye as cyan because it absorbs red wavelengths, and a yellow paint appears yellow because it absorbs blue wavelengths. But when white light falls on a combination of cyan and yellow, then, both red and blue are absorbed, and green is reflected to the eye. Complicated - isn't it?

One fact cannot be denied though: most painters include colours in their palettes which cannot be mixed from yellow, red, and blue paints, and thus do not fit within the RYB colour model. Really colourful greens, cyans, and magentas are impossible to mix, because red, yellow, and blue are not well-spaced around a perceptually uniform colour wheel (acc. to Wikipedia).

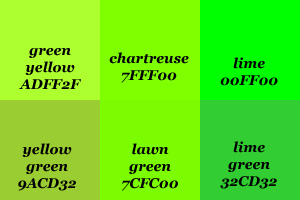

Let's look at some greens from the HTML chart codes and the appropriate names. These make clear that the naming of certain colours is really difficult and so is the determination if you don't have the codes available. The following colour fields also make clear that these colour shades and tints cannot be mixed as paints from yellow and blue paints in order to achieve the same values and brilliance. It is just not that simple.

If you look art the following image you will realize that actually "seagreen" appears much darker than the "dark seagreen". How can this happen other than being a mistake? I really don't know!

The following lighter shades of green do have a larger part of yellow - as you can easily see...

...while the second chart of the lighter versions of greens do contain more blues. Also here it seems hardly understandable why the value of the "light seagreen" seems to be higher than the "dark seagreen". Strange isn't it? The only explanation I have for this is that the eye perceives something different than a photometer does.

Here is another chart where you can see that there are some colours included in the "greens" that I personally would not count into this group but give them a separate grouping: the teals, aquas and turquoises.

(original images source: http://www.toledo-bend.com/colorblind/GreenChart.asp)

Colours are an equally fascinating and difficult subject. Even if I work each day with colours as a painter I use them mostly in a very "emotional" way, hardly with the eye of a scientist. Nevertheless it helps a lot if you know at least some principles about colours in order to be able to find the right "material" for your own work, whether you are an artist, designer or work in any other colour related profession...

~